COVID-19 vaccine development demonstrated how market demand can fire up innovation at dazzling speed. But what about rare diseases and conditions that affect only a small number of people?

That was the question that patients and patient groups started asking U.S. lawmakers in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Mount Sinai researcher Melvin Van Woert and a handful of rare disease patients helped put the issue on the front burner. Woert had developed an effective treatment for the rare neurologic symptom myoclonus – involuntary, jerking muscles. But he ran out of funds to produce the treatment. Woert’s predicament showed how federal policies were failing to support drug development for rare conditions.

Little by little, the issue gained momentum – even inspiring a 1981 episode of the TV drama “Quincy,” a series that featured Jack Klugman as a medical examiner. Eventually, the awakening rare disease community, including scientists and patient advocacy groups, helped convince lawmakers that policy changes were needed. Their efforts resulted in the Orphan Drug Act of 1983. It gives developers of new medicines tax credits for qualified clinical trials; exemption from user fees; and a potential seven years of market exclusivity after approval, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The legislation intended to spark innovation for product development and encourage biotech companies to take a leap into the unknown on products with low market demand.

Now, 37 years later, the FDA has approved about 600 orphan drugs. That’s an accomplishment, but addresses only a fraction of an estimated 7,000 rare conditions. In Europe, the European Medicines Agency also recognizes the need to grant orphan status and does so through the Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products (COMP). Europe offers similar incentives and includes 10 years of market exclusivity.

“More than nine out of 10 orphan products on the market today would never have been developed without the Orphan Drug Act,” said Peter L. Saltonstall, President and CEO of the U.S.-based National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD).

CSL Behring, a global biotech leader specializing in medicines for rare and serious diseases, has received orphan drug designation for several products. In the United States, companies must apply for orphan drug status by submitting a request to the FDA. The process occurs separately from getting a new medicine approved or licensed and, the FDA notes, medicines for rare diseases “go through the same rigorous scientific review process as any other drug for approval or licensing.”

Learn more about orphan drug designation in the United States.

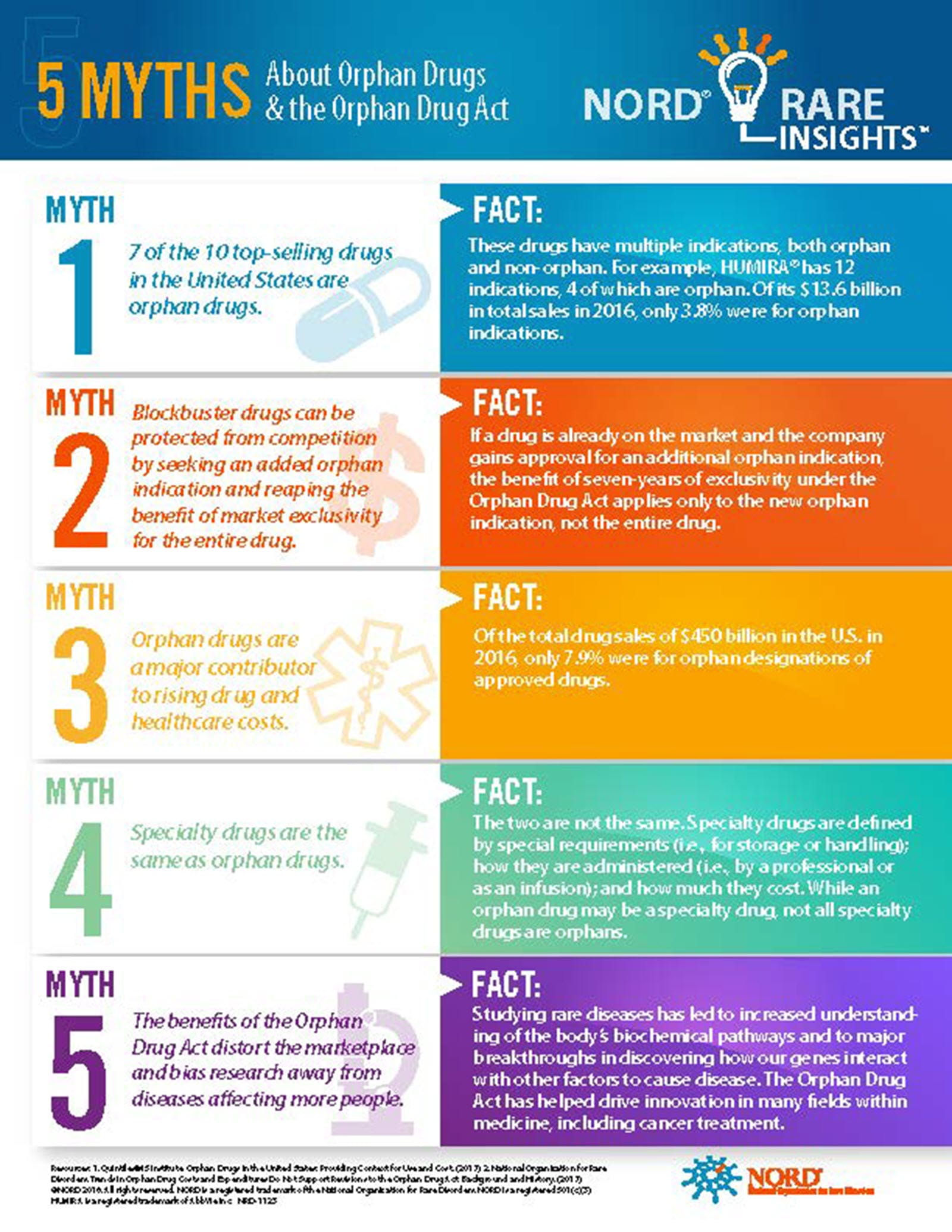

In the infographic below, NORD, which counts 300 patient groups as members, debunks five myths about orphan drugs.