In 2006, you had a couple of options if your loved one was bitten by a venomous snake in Papua New Guinea (PNG).

“You could go to a public health setting like a hospital, roll the dice and hope they had antivenom – which they often didn't. Or you could go to a pharmacy and try and get something off-label and hope it’s the right product, which it often wasn’t. People would be running the risk of going into significant debt to buy life-saving medicines only to end up with antivenoms that were only suitable against Indian snakes,” said Dr. Andrew Watt, co-head at the Australian Venom Research Unit at the University of Melbourne in Melbourne, Australia.

Neither was a great choice, Watt said. But it was the reality of the situation resulting in over 1,000 deaths per year, versus just two in Australia according to the World Health Organization.

“Papua New Guinea has many of the same venomous snakes that we find in Australia. The big difference in Papua New Guinea is that people are much more likely to live where snakes live,” he said. “These communities are nestled in the middle of this beautiful, untouched landscape, so it’s not surprising that you see a higher number of bites occurring.”

Since you can’t change where the snakes are and you can’t change the area where people live, the only thing you can do is ensure there is medicine available, which is exactly what Watt and his small team on the ground in Port Moresby are trying to achieve.

While the Papua New Guinea government has made strides to keep citizens safe and the environment ethical: from banning unsuitable Indian antivenoms to shutting down black market antivenom transactions, they still lacked access to an abundance of life-saving venom antidote.

It was clear they needed an ally in an effort to work towards zero casualties from snakebites.

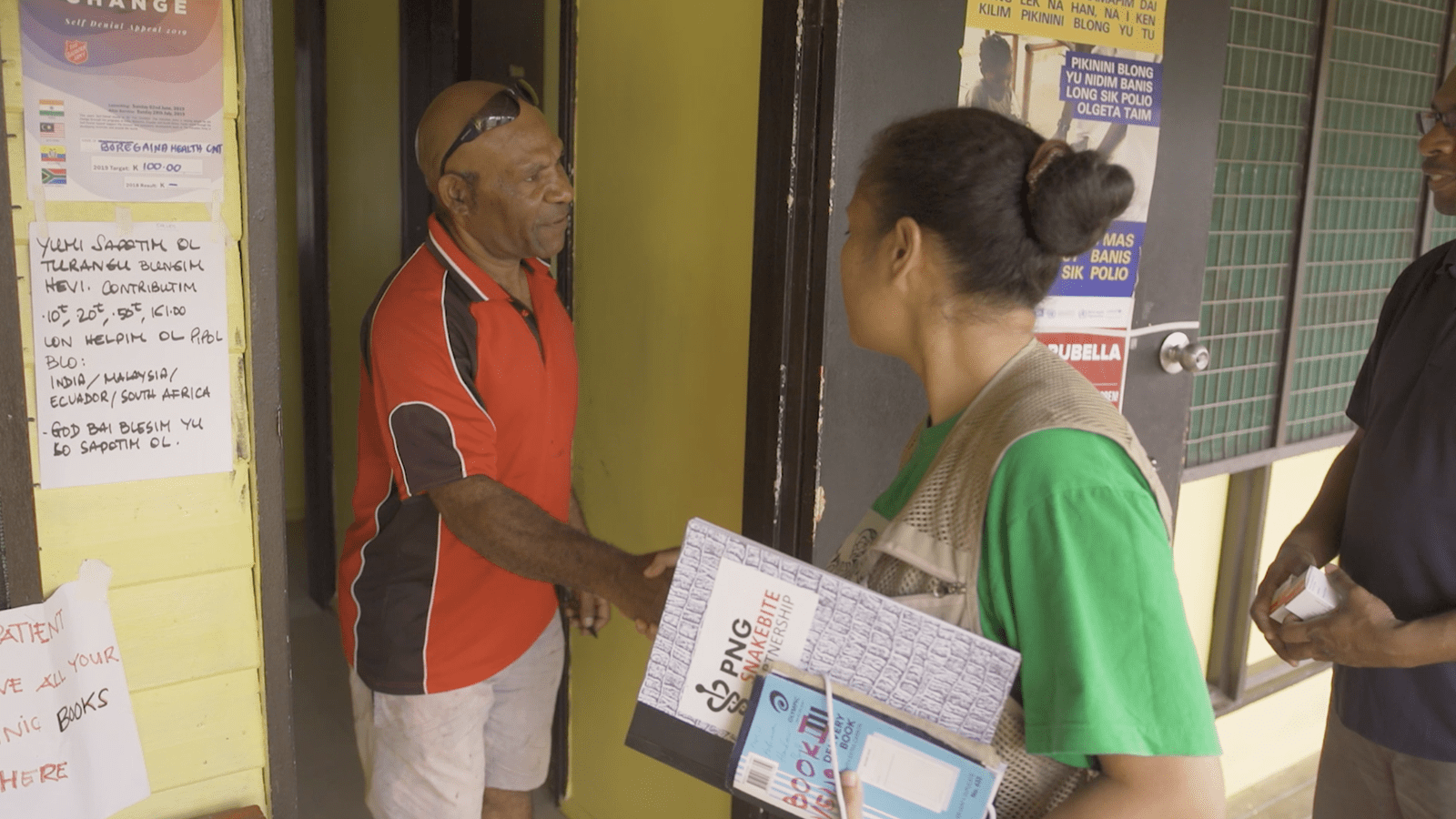

In collaboration with the National Department of Health in PNG and the Australian High Commission, CSL Seqirus, influenza vaccines provider, supplies antivenoms to the Charles Campbell Toxicology Laboratory in PNG where Watt and his local team find creative ways to get it to where it needs to go. Together with locals, they organize antivenom delivery via plane, boat and truck or by foot: if you've got a health center and it's got a fridge, we will try and get product there – that gives us the highest chance of saving lives, Watt explained.

“But there's no use taking medicine there if you can't use it, and so the second part of our work is to train up the health care systems as we go out to health centers and donate antivenom,” he said.

This effort over four years resulted in a tripling in their antivenom supply, and one that mobilized a network of people, processes and places to administer it right within the community that is of zero cost to the person who needs it. In addition, every vial is serialized, tracked and traced to ensure none of it ends up in the wrong hands.

Using the data they’ve complied since 2018 – the year the partnership began - they determined that over 500 lives have been saved. But it’s just the beginning. In 2021, the partnership was renewed for an additional two years, with the goal of solidifying the country’s capacity and sustainability for antivenom supply across Papua New Guinea.

With that extension, Watt and his team have more time to think outside the box and forge an even greater network of trained antivenom administering outposts in even more remote villages.

“What do I see the future holding? And how do we keep the numbers down? We need programs like this to continue,” Watt said.